Émile Durkheim’s The Rules of Sociological Method (1895) marks a milestone in establishing sociology as an autonomous, empirical discipline. While earlier approaches were often philosophical or speculative, Durkheim formulated the foundations for systematic research based on observable, verifiable data. The work remains central for understanding the scientific core of sociology and the role of objective methods.

Scientific Context and Background

Durkheim wrote The Rules at a time when sociology struggled to distinguish itself from philosophy and psychology. He argued that social phenomena should be treated as an independent reality, not reduced to individual motives or metaphysical causes. With this, he set a methodological framework that still shapes the discipline.

Two concepts are especially influential: social facts and emergence. Social facts are patterns external to individuals that exercise constraint; emergence captures that collective phenomena are more than the sum of individual actions and have their own properties and effects.

Key Points

Durkheim’s Social Facts

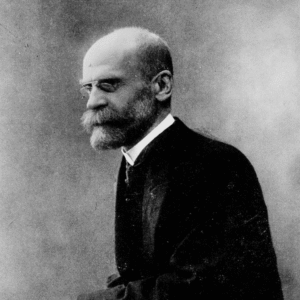

Author: David Émile Durkheim (1858–1917)

First publication: 1895

Country: France

Core idea: Social phenomena exist as things external to individuals and exert constraint; sociology must study them empirically.

Foundational for: theories of deviance and control; functional analysis; later approaches to anomie and social order.

Social Facts: Definition and Properties

At the center of the book is the concept of social facts. For Durkheim, they are “things” that exist independently of any single person and act upon individuals. Typical examples include legal systems, religious rituals, linguistic rules, and social conventions.

- Externality: Social facts exist outside individual consciousness.

- Constraint: They exercise coercive power (sanctions, expectations, moral pressure).

- Generality: They are widespread within a given society.

- Autonomy: They have an existence and logic not reducible to individual psychology.

Durkheim’s notion of emergence highlights that collective phenomena cannot be reduced to the sum of individual actions. A soccer team, for example, is more than just eleven players on the field: strategies, team spirit, and shared expectations create a new social reality that influences each player. Similarly, language rules emerge from collective use and exist beyond any individual speaker.

Crime as a Normal Social Fact

Durkheim’s well-known example is his interpretation of crime. He argues that crime is normal and inevitable in every society because it expresses and tests a community’s moral boundaries. What counts as “criminal” varies over time and between societies; the fact of crime itself does not disappear.

- CrimeActs or omissions that violate criminal laws and are punishable by the state. delineates which behaviors a society defines as deviant, thereby reinforcing the normative order.

- It can play a functional role, strengthening solidarity (e.g., collective reactions to offenses) and sometimes initiating normative change.

- Because definitions of crime are socially constructed and historically variable, acts once punished may later be seen as legitimate or even exemplary.

In this sense, deviant acts can be forerunners of social change. Classic examples include civil rights violations that later appear as moral breakthroughs, or the historical decriminalization of behaviors once prosecuted.

Methodological Rules in Durkheim’s Sense

- Treat social facts as things: Study them as external objects, independent of personal impressions.

- Avoid preconceptions: Bracket common-sense judgments; build concepts from empirical observation.

- Explain social by social: Account for social facts using other social facts (not psychology alone).

- Use systematic observation and data: Base explanations on verifiable evidence and comparative methods.

Durkheim on Crime: Contrary to common assumptions, Durkheim argued that crime is not merely pathological but an inevitable and even useful feature of society.

- Crime marks the boundaries of normative expectations.

- It reinforces solidarity through collective reactions to deviance.

- It can anticipate future moral change — behaviors once criminalized (e.g., homosexuality, civil rights protests – e.g. Rosa ParksRosa Parks (1913–2005) was an African American civil rights activist who became a symbol of resistance against racial segregation after refusing to give up her bus seat to a white passenger in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955. (1955)) may later be seen as legitimate or pioneering.

This functional view remains a cornerstone of criminology and continues to inspire debates on the social role of deviance and crime.

Critical Discussion and Developments

Durkheim’s methodological rigor has been both celebrated and critiqued. Critics argue that strict objectivity and value-freedom are difficult to realize; interpretive traditions emphasize the need to understand subjective meanings. Nonetheless, Durkheim’s framework remains foundational for empirical social research and for clarifying the distinct object and methods of sociology.

Application and Examples

Durkheim implemented these principles in Suicide (1897), where he analyzed cross-national suicide rates to show how social integration and anomie shape individual action. Contemporary studies across inequality, social structure, and norm change continue to build on these methodological foundations.

Links to Contemporary Megatrends

- Social inequality & exclusion: Empirical, Durkheimian methods help analyze the causes and patterns of inequality.

- Social structure & socialization: Social facts shape socialization and position individuals within social structure.

- NormsNorms are socially shared rules or expectations that guide and regulate behavior within a group or society. and values: Methodical observation clarifies how moral orders change over time.

Takeaway: Lasting Significance for Sociology

The Rules of Sociological Method remains essential reading for anyone studying society scientifically. Durkheim not only helped found an empirical sociology; he also articulated its methodological self-understanding. The idea of emergence continues to be key for grasping complex social processes. For students, the book offers a blueprint for structuring and conducting objective research.

Together with The Division of Labour in SocietyA group of individuals connected by shared institutions, culture, and norms. (1893) and Suicide (1897), it forms the core of Durkheim’s methodological and theoretical contributions to sociology.

Literature

- Durkheim, Émile (1982). The Rules of Sociological Method. Edited with an Introduction by Steven Lukes. Translated by W.D. Halls. New York: Free Press.

- Durkheim, Émile (1897/2006). Suicide: A Study in Sociology. London/New York: Routledge.