Prisons are among the most visible and contested institutions of modern societies. They represent the state’s ultimate power to deprive individuals of liberty, justified in the name of justice, order, and security. Yet the prison is not a timeless or natural institution: it emerged historically under specific social, political, and cultural conditions. In criminology and sociology, imprisonment has been studied both as a practice of punishment and as a wider mechanism of social control. This article explores the historical development of the modern prison, its role as a total institution, critical perspectives on incarceration, and the debates surrounding abolitionism and alternatives to imprisonment.

Prisons, Imprisonment and Alternatives

- Disciplines: CriminologyThe scientific study of crime, criminal behavior, prevention, and societal reactions to deviance within and beyond the criminal justice system., Sociology, Political Science

- Historical roots: Walnut Street Jail (1790), Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, rise of modern penitentiaries in the 19th century

- Core concepts: PunishmentThe imposition of a penalty in response to an offense or crime, intended to deter, reform, or incapacitate., social control, legitimacy, rehabilitation, prison-industrial complex

- Theories: Foucault’s disciplinary power, Goffman’s total institution, Critical CriminologyA perspective that examines power, inequality, and social justice in understanding crime and the criminal justice system., AbolitionismA movement advocating for the elimination of prisons and punitive justice systems in favor of transformative, community-based approaches.

- Key works:

Discipline and Punish (Foucault, 1975);

Asylums (Goffman, 1961);

The Felon (Irwin, 1970);

Being Mentally Ill (Scheff, 1966);

Crime Control as Industry (Christie, 1993);

Punishing the Poor (Wacquant, 2009);

Are Prisons Obsolete? (Davis, 2003);

The Politics of Abolition (Mathiesen, 1974) - Essential reading: Jewkes, Y., Bennett, J., & Crewe, B. (Eds.). (2016). Handbook on Prisons; Liebling, A., & Maruna, S. (Eds.). (2005). The Effects of Imprisonment; Coyle, A., Fair, H., Jacobson, J., & Walmsley, R. (2016). Imprisonment Worldwide.

- Contemporary debates: Mass incarceration, racial disparities, prison privatization, abolitionism, restorative justice, electronic monitoring, alternatives to imprisonment

Historical Development

The modern prison was “invented” at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Walnut Street Jail in Philadelphia (1790) is often regarded as the first penitentiary, designed to isolate offenders, enforce labour, and promote moral reform. Religious groups, especially the Quakers, played an influential role in shaping this model: imprisonment was understood as an opportunity for reflection, repentance, and ultimately moral rehabilitation. This spiritual dimension is reflected in the very term “penitentiary,” derived from “penitence.” This early model illustrates how imprisonment was framed not only as punishment, but also as a moral and social project.

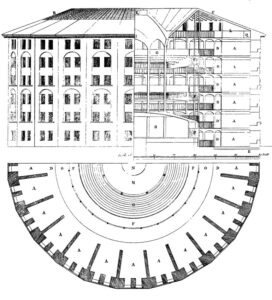

Jeremy Bentham (1791), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Around the same time, Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon presented a model of surveillance that would later become emblematic of disciplinary societies: prisoners internalise control because they never know if they are being watched. Alongside penitentiaries, early workhouses and houses of correction linked punishment to labour, reflecting the emerging capitalist ethos that discipline and productivity were central to reform. These innovations marked a shift away from corporal punishment, banishment, or execution towards incarceration as the central form of state punishment. As Michel Foucault (1975) argued, the prison exemplifies the broader transformation from sovereign power to disciplinary power in modernity.

Infobox: The Invention of the Modern Prison

- Walnut Street Jail (Philadelphia, 1790): Often considered the first modern penitentiary. Emphasised solitary confinement, labour, and moral reform, shifting punishment from public spectacle to institutional discipline.

- Eastern State Penitentiary (Philadelphia, 1829): Landmark prison built on a radial plan, institutionalising the Pennsylvania System of solitary confinement and silent reflection. Criticised for its psychological effects on inmates.

- Pennsylvania vs. Auburn System: The Pennsylvania System enforced isolation and solitary labour to promote penitence, while the Auburn System combined group labour during the day (under strict silence) with solitary confinement at night. The Auburn model proved more cost-efficient and became dominant in the United States.

- Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon (1791): A theoretical prison design based on constant visibility and surveillance. Prisoners internalise discipline because they never know if they are being watched.

- Shift from corporal to institutional punishment: The transition from executions, corporal punishment, and banishment to long-term imprisonment reflected broader trends of modernity, rationalisation, and state power.

- Michel Foucault (1975): In Discipline and Punish, Foucault interpreted prisons as emblematic of a new disciplinary society, where surveillance and control extend beyond prisons into schools, factories, and the military.

- Further developments:

From the 19th century onwards, prisons evolved through the abolition of debtors’ prisons, the rise of reformatories and juvenile institutions, the Progressive Era innovations of probation and parole, the post-war focus on rehabilitation, the U.S. era of mass incarceration from the 1970s, and contemporary movements towards alternatives and decarceration.

Prisons as Total Institutions

Prisons are not merely buildings but complex organisations that structure every aspect of daily life. Erving Goffman’s concept of the “total institution” describes how inmates are cut off from society, live under constant surveillance, and are subject to rigid routines. Imprisonment often leads to stigma, both during incarceration and after release, shaping the life chances of ex-prisoners (Goffman, 1963; Irwin, 1970). Studies of juvenile justice (Cicourel, 1968) and mental health institutions (Scheff, 1966) further highlight how imprisonment reflects broader mechanisms of categorisation and social exclusion.

An equally influential perspective comes from Gresham Sykes, who in his classic study The SocietyA group of individuals connected by shared institutions, culture, and norms. of Captives (1958/1971) analysed the lived experiences of inmates in a maximum-security prison. He identified five central “pains of imprisonment”: the deprivation of liberty, of goods and services, of heterosexual relationships, of autonomy, and of security. Together, these deprivations undermine prisoners’ sense of self and create the specific social world of the prison. The deprivation model complements Goffman’s notion of the mortification of the self by illustrating how imprisonment not only separates individuals from society but also systematically reshapes their identities and interactions within the prison walls.

Infobox: Gresham Sykes – The Pains of Imprisonment

- Deprivation of liberty: The most obvious loss is freedom itself. Prisoners are confined both by the walls of the institution and by the rigid routines inside. Movement is restricted, contact with family and community is limited, and release is uncertain. This double confinement creates a profound sense of exclusion from wider society.

- Deprivation of goods and services: Access to material possessions and everyday services is tightly controlled. Inmates live with only a few permitted items, and consumption, leisure, or comfort are severely restricted. In a consumer society, this deprivation reinforces feelings of loss and marginalisation.

- Deprivation of heterosexual relationships: Imprisonment cuts individuals off from partners and intimacy. Beyond sexuality, this deprivation symbolises a rupture in emotional bonds and family life. Sykes described this loss as a figurative “castration,” underlining its psychological weight.

- Deprivation of autonomy: Daily life in prison is governed by strict routines and orders. From waking and eating to working and exercising, almost every activity is scheduled and supervised. The absence of choice erodes personal autonomy and fosters dependency on institutional authority.

- Deprivation of security: Despite their high walls, prisons are not safe places. Inmates are forced into close contact with others who may have long histories of violence or aggression. The resulting atmosphere of threat, tension, and vulnerability undermines feelings of safety and stability.

Together, these five deprivations shape what Sykes (1958/1971) called the “society of captives.” They reveal how imprisonment not only punishes through loss of freedom but also restructures identity, relationships, and daily life in profound ways.

Critiques of the Prison System

Despite their centrality in modern justice systems, prisons have long been criticised from practical, social, and theoretical perspectives. These critiques reveal that imprisonment often fails to achieve its stated goals and instead produces a range of negative consequences.

Practical problems

- Overcrowding and poor conditions: Chronic overcrowding, violence, and inadequate healthcare raise serious human rights concerns in many countries.

- Cost and inefficiency: Prisons are extremely expensive to build and operate, absorbing resources with limited evidence of effectiveness in reducing crime.

- Criminogenic effects: Imprisonment can reinforce criminal identities, strengthen prison subcultures, and create networks that sustain offending after release.

Social consequences

- Stigmatisation and collateral damage: A prison sentence often results in long-term exclusion from employment, housing, and civic life, extending punishment far beyond release.

- Disproportionate impact: Incarceration affects minorities, migrants, the poor, and people with mental health or substance problems disproportionately.

- Gendered critique: Women face specific hardships such as inadequate healthcare, separation from children, and regimes designed for men.

Theoretical critiques

- Symbolic function: Following Durkheim and Foucault, critics argue that prisons serve less to rehabilitate than to demonstrate state authority and discipline.

- Political economy: Nils Christie (1993) described prisons as part of a growing “crime control industry,” while Loïc Wacquant (2009) analysed mass incarceration as a strategy of social marginalisation in neoliberal societies.

Abolitionist perspectives

- Fundamental critique: Scholars such as Angela Y. Davis and Thomas Mathiesen argue that prisons are obsolete institutions that perpetuate injustice, calling instead for alternatives such as restorative justice and community-based sanctions.

Global incarceration rates

For comparative context, the table below summarises the most recent prison population rates (prisoners per 100,000 population) for selected countries based on the World Prison Brief. Data points refer to the latest year available for each country and are not always from the same reference date.

| Country | Prison population rate (per 100,000) | Year of data | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 541 | 2022 | World Prison Brief |

| Russian Federation | 300 | 2023 | World Prison Brief |

| Brazil | 416 | 2024 | World Prison Brief |

| United Kingdom (England & Wales) | 142 | 2025 | World Prison Brief |

| Germany | 71 | 2024 | World Prison Brief |

| Norway | 54 | 2025 | World Prison Brief |

| Sweden | 92 | 2024 | World Prison Brief |

| Finland | 54 | 2024 | World Prison Brief |

| Australia | 163 | 2024 | World Prison Brief |

| South Africa | 260 | 2025 | World Prison Brief |

| Nigeria | 35 | 2025 | World Prison Brief |

| Rwanda | 620 | 2024 | World Prison Brief |

The comparison of prison population rates reveals striking global differences. The United States remains exceptional with more than 500 prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants, far outpacing other industrialised nations. This reflects the phenomenon of mass incarceration, marked by racial disparities and the expansion of punitive policies since the 1970s.

In Russia, the rate is significantly lower than in the 1990s but still high by European standards. The system reflects a historical legacy of penal colonies and the continued use of imprisonment as a primary sanction. Brazil has also seen rapid growth in its prison population: overcrowding, violence, and the role of organised crime shape a system under constant pressure.

England and Wales stand out in the European context with a relatively high rate of around 140 per 100,000. Long-standing debates over privatisation, overcrowding, and punitive sentencing keep incarceration firmly on the political agenda. Germany, by contrast, reports a rate below 80, reflecting a tradition of proportionality and rehabilitation within a broader welfare state framework.

The Nordic countries represent the opposite end of the spectrum. Norway and Finland maintain very low rates (around 50 per 100,000), underpinned by the normalisation principle, which emphasises reintegration and humane prison conditions. Sweden, however, no longer appears quite as exceptional: its rate has risen to over 90, partly in response to growing political and public pressure over gang-related crime and shootings. The Swedish case illustrates how changing crime patterns and political climates can quickly alter incarceration policies, even in countries with traditionally low rates.

Australia occupies a middle position with a rate around 160. The most striking feature here is the overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples, who constitute a small minority of the population but a large share of prisoners. South Africa shows high rates (around 260), a legacy of the Apartheid system combined with persistent inequality and high levels of violent crime.

More surprising are the extremes at the lower and upper ends. Nigeria reports one of the world’s lowest prison population rates (around 35), but this number is misleading: overcrowding is severe, because more than two-thirds of inmates are held in pre-trial detention for extended periods. Rwanda, in contrast, records one of the highest rates (above 600), reflecting the legacy of mass incarceration following the 1994 genocide. These cases show that prison population rates cannot be understood as simple indicators of crime or punishment; they must be interpreted in the light of history, politics, and institutional practices.

Overall, the table illustrates the diversity of imprisonment worldwide. While some countries rely heavily on incarceration as a default sanction, others maintain low rates by investing in alternatives, welfare structures, and reintegration. This divergence underscores that prison is not an inevitable response to crime but a policy choice embedded in broader social and political contexts.

The U.S. prison system: institutions and levels

The United States warrants a closer look because it has the highest incarceration rate among industrialised nations and has become a global symbol of mass incarceration. Understanding the structure of the U.S. prison system is therefore crucial for comparative criminology: it illustrates how a wealthy democracy has developed a penal landscape of unparalleled scale, complexity, and controversy.

The U.S. penal system is multi-layered, with distinct jurisdictions and facility types:

- Jails vs. prisons: Jails are locally run (county/city) facilities holding pre-trial detainees and those serving short sentences (typically less than one year). Prisons are state or federal facilities for longer sentences following conviction (Bureau of Justice Statistics, n.d.-a).

- Jurisdictions: State prisons hold the majority of sentenced prisoners under state law; the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) houses those convicted of federal offences. In addition, there are tribal/Indian Country jails and specialised detention facilities (Bureau of Justice Statistics, n.d.-a).

- SecurityProtection from threats, harm, or danger. levels: U.S. prisons are classified into minimum, low, medium, and high (maximum) security levels. At the apex are supermax facilities such as ADX Florence, where inmates are held under near-total isolation (Wikipedia, 2024).

- Privatisation and capacity pressures: Several states contract private companies to manage facilities. Chronic overcrowding, violence, and deteriorating infrastructure have repeatedly triggered debates about prison closures and reform (AP News, 2021).

U.S. at a glance

- Scale: The U.S. remains a global leader in per capita incarceration, with rates several times higher than most European countries (The Sentencing Project, 2022).

- Data caveats: Official reporting on issues such as deaths in custody remains inconsistent, complicating oversight and international comparisons (Chadha, 2022).

Social consequences of mass incarceration

Research consistently shows that incarceration shapes life chances far beyond the sentence itself. It concentrates among disadvantaged communities and radiates through families and neighbourhoods:

- Lifetime risk of incarceration: According to U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates, nearly one in three African American men born in the late 20th century could expect to be imprisoned during their lifetime, compared to one in 17 white men (Bonczar, 2003). This stark disparity illustrates how mass incarceration functions as a mechanism of racial inequality.

- Racialised impact: Disproportionate incarceration of Black and Latino men has become a key driver of cumulative racial inequality in income, employment, health, and civic participation.

- Family disruption: Imprisonment removes caregivers and earners, increasing household instability and poverty; for many young Black men in poor urban areas, prison has become a “normalised” life-course event, with intergenerational effects on children’s outcomes.

- Labour market exclusion: A prison record often reduces employment prospects, creating barriers to reintegration and sustaining cycles of poverty and recidivism.

- Housing insecurity: Former prisoners face restricted access to stable housing, both through formal policies and informal discrimination.

- Civic exclusion: In many jurisdictions, imprisonment entails the loss of political rights, including disenfranchisement from voting, which weakens democratic participation.

- Community destabilisation: High incarceration rates in specific neighbourhoods disrupt social networks, leading to instability and the erosion of collective efficacy.

- Health effects: Incarceration is linked to higher risks of chronic illness, mental health problems, and reduced life expectancy, with effects extending to prisoners’ families.

- GenderSocial and cultural roles, behaviors, and expectations linked to masculinity and femininity.-specific consequences: Women in prison experience distinct hardships, particularly the separation from children and lack of appropriate healthcare, while children of incarcerated mothers face heightened risks.

Overall, mass incarceration functions not only as a penal practice but also as a mechanism of social stratification, reproducing disadvantage and inequality across generations.

Why Scandinavian incarceration is lower

Nordic countries (e.g., Norway, Sweden, Finland) combine low prison rates with a normalisation philosophy:

- Normalisation principle: “The punishment is the restriction of liberty; otherwise, life should resemble life outside as much as possible” — including education, health care, and social services delivered via an “import model” from the community (Norwegian Correctional Service, n.d.).

- Lowest necessary security: Placement at the lowest security level consistent with safety; emphasis on reintegration and desistance over mere incapacitation (Wikipedia, 2024).

- Outcomes and debate: International commentary often links these principles to comparatively lower recidivism, though measurement methods differ and scholars caution against easy causality claims (Høidal, 2019).

Prisons that (officially) don’t exist: off-ledger detention

Global prison statistics can miss facilities operating outside transparent legal oversight. Examples frequently cited by human rights monitors include:

Shane T. McCoy, U.S. Navy, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- China (Xinjiang): Mass arbitrary detention of Uyghurs and other minorities in a network of facilities documented by UN bodies and independent experts, with grave human-rights concerns (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human RightsFundamental rights and freedoms to which all human beings are entitled, regardless of nationality, gender, or social status., 2022).

- North Korea: Secretive kwan-li-so political prison camps with systematic abuses, forced labour, and denial of basic liberties (Human Rights Watch, 2023a).

- Russia: Penal colonies used against dissidents, a growing roster of political prisoners, and credible reports of torture and ill-treatment in detention (Human Rights Watch, 2024).

- United States (Guantánamo Bay and “black sites”): The U.S. detention facility at Guantánamo Bay has been criticised for indefinite detention without trial and allegations of torture. In addition, so-called CIA “black sites” operated in several countries after 9/11The September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States, which profoundly transformed security policies worldwide., where detainees were held secretly and outside judicial oversight (Human Rights Watch, 2023b).

These cases illustrate that any global comparison must consider opacity and non-standard forms of detention that are undercounted or excluded from official series.

Abolitionism and Alternatives

The critique of prisons culminated in abolitionist movements, questioning whether prisons should exist at all. Angela Y. Davis (2003) argued that prisons are obsolete as instruments of justice, serving instead as tools of racial and social domination. Similarly, Thomas Mathiesen (1974) developed the idea of a continuous struggle against the prison system, advocating for “unfinished alternatives.” Alternatives to imprisonment include probation, community service, restorative justice, fines, treatment programs, and electronic monitoring. These measures aim to reduce prison populations, promote rehabilitation, and avoid the criminogenic effects of incarceration.

Alternatives to Imprisonment

- Probation: Conditional suspension of a prison sentence, focusing on supervision, rehabilitation, and reintegration.

- Community service: Offenders perform unpaid work as a form of reparation to society instead of serving time in prison.

- Restorative justice: Emphasises repairing harm through dialogue, mediation, and agreements between offenders, victims, and communities.

- Electronic monitoring: Use of ankle bracelets and digital technologies to restrict movement while avoiding full incarceration.

- Fines and day-fines: Monetary sanctions scaled to income and offence severity; widely used in European countries.

- Treatment programs: Diversion into therapeutic or educational interventions (e.g., drug courts, anger management) instead of imprisonment.

- Goal: Reduce overcrowding, address social causes of crime, enhance reintegration, and avoid the criminogenic effects of imprisonment.

Contemporary Challenges

Today, prisons face a series of pressing challenges that reflect broader social, political, and technological transformations. Mass incarceration, particularly in the United States but also in Brazil, Russia, and parts of Africa, has generated widespread debate about human rights, prison conditions, and systemic racism. These debates intersect with growing concern over overcrowding, poor healthcare, and inadequate rehabilitation opportunities, which remain persistent in many prison systems worldwide (Jewkes et al., 2016).

The privatisation of prisons introduces further controversy. Private companies are contracted to build or manage facilities in countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia, raising questions about accountability, profit motives, and whether commercial interests undermine rehabilitation. Critics argue that financial incentives perpetuate high incarceration rates rather than support decarceration or community-based alternatives (Christie, 1993).

Technological change adds another layer of complexity. Electronic surveillance, GPS monitoring, predictive policing, and algorithmic risk assessments extend penal control beyond prison walls into everyday life. While these technologies are often promoted as cost-efficient alternatives to incarceration, scholars warn of new forms of inequality, bias, and “net-widening,” where more individuals are subjected to control measures (Hannah-Moffat, 2019).

Issues of gender, race, and class remain deeply embedded in imprisonment practices. Women face regimes largely designed for men and often experience specific harms such as separation from children and lack of appropriate healthcare. Minority and disadvantaged groups are overrepresented in most prison populations, illustrating how punishment intersects with structural inequality (Western, 2006; Wacquant, 2009). The criminalisation of migration has further blurred the lines between criminal justice and immigration control, producing hybrid forms of detention that are not always captured in official statistics.

Another pressing challenge concerns prison gangs and subcultures, which structure inmate societies through informal codes, protection networks, and illicit economies. While gangs can provide safety in violent environments, they also reinforce criminal identities, undermine rehabilitation, and extend their influence beyond prison walls into communities (Fleisher & Decker, 2001; Crewe, 2009).

A further issue is the ageing prison population. Longer sentences and stricter parole regimes have produced growing numbers of elderly inmates, especially in the United States, Europe, and Japan. This demographic shift raises questions about proportionality, human rights, and the financial burden of providing adequate healthcare and custodial care for ageing prisoners (Aday & Krabill, 2011; Wahidin, 2004).

Finally, climate change, pandemics, and global insecurity have become new challenges for prison systems. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed the vulnerability of overcrowded facilities, leading to emergency releases in some countries. Climate-related disasters increasingly threaten ageing prison infrastructures. These developments underline that imprisonment is not a static institution but a dynamic, contested, and deeply political practice—one that will continue to shape, and be shaped by, wider struggles over security, justice, and social order (Fraser & Matthews, 2021).

Conclusion

Prisons are central to the modern criminal justice system but also a focal point of critique and resistance. Their historical invention as disciplinary institutions, their operation as total institutions, and their role in reproducing inequality all make them crucial objects of criminological inquiry. At the same time, abolitionist perspectives and alternative sanctions demonstrate that imprisonment is neither inevitable nor the only way to respond to crime. For criminology, the challenge is to critically analyse how imprisonment sustains and destabilises social order, and to explore pathways towards more just and humane forms of social control.

Literature

- Aday, R. H., & Krabill, J. J. (2011). Women aging in prison: A neglected population in the correctional system. Lynne Rienner.

- AP News. (2021, September 15). Mississippi closes notorious Unit 32 at Parchman prison. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/c02c96b6f6a3c5535cc3e3025d5d2585

- Bonczar, T. P. (2003). Prevalence of imprisonment in the U.S. population, 1974–2001 (Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report, NCJ 197976). U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/piusp01.pdf

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. (n.d.-a). Correctional institutions. U.S. Department of Justice. https://bjs.ojp.gov/topics/corrections/correctional-institutions

- Chadha, J. (2022, September 20). Deaths in prisons and jails are rising. But the government isn’t keeping count. TIME. https://time.com/6215142/deaths-prisons-jails-justice/

- Christie, N. (1993). Crime control as industry: Towards Gulags, Western style? Routledge.

- Clear, T. R. (2007). Imprisoning communities: How mass incarceration makes disadvantaged neighborhoods worse. Oxford University Press.

- Crewe, B. (2009). The prisoner society: Power, adaptation and social life in an English prison. Oxford University Press.

- Davis, A. Y. (2003). Are prisons obsolete? Seven Stories Press.

- Fleisher, M. S., & Decker, S. H. (2001). An overview of the challenge of prison gangs. Corrections Management Quarterly, 5(1), 1–9.

- Foucault, M. (1975). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). Pantheon.

- Fraser, A., & Matthews, B. (2021). Carceral climate justice: Climate change and the future of prison abolition. Critical Criminology, 29(4), 765–781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-021-09585-5

- Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. Anchor Books.

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice-Hall.

- Hagan, J., & Dinovitzer, R. (1999). Collateral consequences of imprisonment for children, communities, and prisoners. Crime and Justice, 26, 121–162. https://doi.org/10.1086/449296

- Hannah-Moffat, K. (2019). Algorithmic risk governance: Big data analytics, race and information activism in criminal justice debates. Theoretical Criminology, 23(4), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480619827548

- Høidal, A. (2019). Norway’s model of incarceration: A humane approach to prison? Eastern Kentucky University Encompass. https://encompass.eku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1680&context=honors_theses

- Human Rights Watch. (2023a). World Report 2023: North Korea. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/north-korea

- Human Rights Watch. (2023b). Q&A: Guantanamo Bay, black sites, and torture. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/01/11/qa-guantanamo-bay-black-sites-and-torture

- Human Rights Watch. (2024). World Report 2024: Russia. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2024/country-chapters/russia

- Irwin, J. (1970). The felon. Prentice-Hall.

- Jewkes, Y., Bennett, J., & Crewe, B. (Eds.). (2016). Handbook on prisons (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Mathiesen, T. (1974). The politics of abolition. Martin Robertson.

- Norwegian Correctional Service. (n.d.). About the Norwegian Correctional Service. https://www.kriminalomsorgen.no/about-the-norwegian-correctional-service.6327382-536003.html

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2022). OHCHR assessment of human rights concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China. United Nations. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/09/xinjiang-report-china-must-address-grave-human-rights-violations-and-world

- Pager, D. (2003). The mark of a criminal record. American Journal of Sociology, 108(5), 937–975. https://doi.org/10.1086/374403

- Pettit, B., & Western, B. (2004). Mass imprisonment and the life course: Race and class inequality in U.S. incarceration. American Sociological Review, 69(2), 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240406900201

- Scheff, T. J. (1966). Being mentally ill: A sociological theory. Aldine.

- Schnittker, J., Massoglia, M., & Uggen, C. (2012). Out and down: Incarceration and psychiatric disorders. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53(4), 448–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146512453928

- Sykes, G. M. (1971). The society of captives: A study of a maximum security prison. Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1958)

- The Sentencing Project. (2022). Mass incarceration trends. The Sentencing Project. https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/mass-incarceration-trends/

- Wakefield, S., & Wildeman, C. (2014). Children of the prison boom: Mass incarceration and the future of American inequality. Oxford University Press.

- Wacquant, L. (2009). Punishing the poor: The neoliberal government of social insecurity. Duke University Press.

- Wahidin, A. (2004). Older women in the criminal justice system: Running out of time. Jessica Kingsley.

- Western, B. (2006). Punishment and inequality in America. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Western, B., & Pettit, B. (2010). Incarceration and social inequality. Daedalus, 139(3), 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00019

- Wikipedia. (2024, January 22). Normality principle. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Normality_principle

- Wikipedia. (2024, February 1). ADX Florence. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ADX_Florence